Carnegie Art Award 2014

Interview with Dag Erik Elgin, by Mika Hannula

BALANCE OF PAINTERS

This year, Norwegian artist Dag Erik Elgin wins the Carnegie Art Award first prize of one million Swedish kronor, one of the world’s largest art awards, for a work filled with humour, history and science.

This is the eleventh edition of the Carnegie Art Award for the most prominent Nordic artists, and the opening of the eleventh exhibition, Carnegie Art Award 2014, featuring 17 Nordic artists selected in tough competition among 113 nominees. Elgin is showing a monumental work, which communicates both with the French artist, art critic and diplomat Roger de Piles’ (1635-1709) quantitative system (based on a scale from 0 to 18, and divided into the categories “composition”, “drawing”, “colour” and “expression”) of the most important artists of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, and with the minimalism and conceptualism of our time. The series Balance of Painters is a painted version of de Piles’ overview. Elgin is currently working on a large research and exhibition project at Henie Onstad Kunsesenter concerning the provenance of works by Henri Matisse.

Mika Hannula: Your series of works at the Carnegie exhibition, The Balance of Painters, refers directly to the book by the same name written by Roger de Piles (1635-1709) who appended a list of fifty-six major painters of his time, with whose work he had acquainted himself as a connoisseur during his travels.

How did you find or encounter this person and his book? What was it that first captured your attention?

Dag Erik Elgin: Painting’s ability to provoke dialogue has always interested me. From Vasari to Buchloh we can trace an unbroken line of texts informed by painting, engaging in massive text-driven painterly post-production. The book The Balance of Painters, (1708) is unique in that de Piles actually created imagery in text when combining numbers to characterise the prominent painters of his day. In doing so, the image was re-established on its own terms within the discourse – expressed by the term “balance”. For The Balance of Painters is not solely a collection of separate numbers, but rather a precise visual expression of an exact balance between composition, drawing, colour and expression. It was as if this material was just waiting to be exposed to a painterly investigation.

MH: Roger de Piles was searching for a system, a universal system for criteria and quality. Each painter on the list was given marks from 0 to 18 for composition, drawing, colour and expression. Are these relevant criteria for you?

DEE: The fact that contemporary art no longer operates with medium-specific criteria does not mean that the art world refrains from applying universal systems. On the contrary, it seems that the 21st century is obsessed with ranking, rating and positioning. As for medium-specific criteria, I personally take great pleasure in drawing and painting. I find they are excellent means of communication, but this doesn’t mean a specific set of criteria can be deduced from a highly personal practice, to dictate a norm. I do believe that specific criteria exist; not as a given, but as a consequence of a specific practice – an unrepeatable practice that seems to arise out of a personal urgency.

MH: Can we detect a kind of lasting fascination, or obsession, even, with the numbers and their promised logic of coherence and clarity here?

DEE: The backdrop for The Balance of Painters is no doubt rationalist and early Enlightenment. But again, I find de Piles’ way of expressing “Quality” via the metaphor of “Balance” to be crucial, demonstrating that it is all about the exact weight of four numbers rather than the abstract weight expressed in one single number. It is not about numerology, but rather about finding an exact image for his specific concept – that is, the visual expression of a renowned artist’s complete oeuvre to be taken in at one glance.

MH: Traditions of painting, as in plural. What does this mean to you? How has this ongoing engagement with the traditions changed in your work through the years?

DEE: That’s a huge question, and I will try to give you an answer. Ever since Cimabue and Giotto, painting has been linked to tradition, in the sense that each new generation is built on the experience of its predecessors, which has both its pros and cons. A positive side, for example, is that it was on the basis of Giorgione’s investigations that Titian could concentrate on specific painterly issues and thus develop his rich, sensuous painterly language. On the other hand, tradition can never explain an artist like Titian. His work has an element of coming over as new and surprisingly fresh, as if being performed right there in front of our eyes. In great art there is always an element of dysfunction that seems to evade tradition.

To a certain extent, this malfunction was instrumentalised by modernist strategies that introduced the speculative error, which actually might lead to a new kind of academism. So how does one engage with tradition? My answer would probably be by building up a body of work where concepts and ideas are put to the test through the daily practice of painting. And then hoping for some great dysfunctions to occur…

MH: Dysfunctions? Can you be a bit more specific – perhaps in relation to The Balance of Painters series?

DEE: You lead me into dangerous territory since I just criticised the instrumentalisation of error. I believe dysfunction could save us from professionalism, but it does not exclude method. On the contrary, it is on the basis of method that interesting deviations can occur. It seems significant that Matisse kept one of Cézanne’s Bathers in his private collection throughout his life, because, as he said, he was touched by it. It is an unspectacular, almost private little painting; rough brushstrokes without bravura. The piece is obviously not meant to impress and rather possesses an element of amateurism in the sense that it is painted with deep tenderness. On the other hand, you could hardly find a more method-based painter than Cézanne. But it is if his greatest works surpass method, and almost physically touch the viewer.

You have to excuse me for serving anecdotes rather than elaborating on possible dysfunctions in my own works, but the essential thing is that it is experienced by the receiver rather than by the sender.

MH: There is an undeniable seriality in your way of working, although you prefer to label it as sequence. What is the difference between these two concepts for you?

DEE: The distinction between seriality and sequence was important to me in an earlier series called Sinthome (2002) in that I wanted to bring together a sequence of highly different imagery in the manner in which the works had been executed. To me, seriality is more closely linked to repetition and neutrality evoking minimal strategies.

MH: Another striking characteristic in your way of working is your conceptual approach. But what kind of a “conceptualist” are you? Is it a strategy, or a method? And what role does the actual act of painting, the physical act of relating to materials, play in this process?

DEE: Great paintings always evoke a specific physicality, a heightened tactile, often sensuous experience. This effect can be direct and obvious like, say, in a painting by Ryman or Pollock. But I am also interested in seemingly cold conceptualists who are not that cold after all, like On Kawara, Remy Zaugg or certain paintings executed by Art&Language. It is a great painterly strategy to leave space for the viewer to rediscover haptic qualities in an apparentlyantiseptic, or straightforward, boring material informed by the aesthetics of administration.

The closest I come to a painterly method is perhaps in the series Originals (2012) where I repainted modernist icons in order to fully comprehend the processes that led to a specific painting. At first glance, this might seem like a set strategy, but it inevitably takes me to places I have never been before as a painter.

STOP FOR A MOMENT

PAINTING AS A PLACE TO BE

NIFCA-Nordic Institute for Contemporary Art 2002

Kari Immonen (KI): What’s your relationship to tradition?

Dag Erik Elgin (DEE): Painting comprises a vast and illustrious tradition, which you are unavoidably made a part of. You are entering a field as soon as you start producing art, which not only carries with it the weight of its own history, but also represents a medium that has lost its privileged position. This burden can become too heavy and one has to be aware of the necessity to leave some of the historical baggage behind.

Basically, one should be well informed without over-indulging in historical nostalgia. At the same time, it should be allowed to act freely, move forward and do something which is not necessarily ‘new’ but which has actuality and lends itself to dialogue.

(KI) Maybe the younger generation has a more relaxed manner of working, without too many overly serious viewpoints about the death of painting, commercialism, painting’s status and other related matters?

(DEE) Even the so-called new media are encumbered with convention, genre and tradition. So, in a sense, painting can be said to have lost some of its purely anachronistic stance and has simply become one among many co-existing aesthetic practises. The abandoning of conventional genre divisions and the shift towards inter-medial art practices not only open up the field, they also put the emphasis on content, ideas, concepts rather than on media-specific strategies.

(KI) But the opinions towards and about painting still seem to be heated?

(DEE) I have never accepted that painting cannot ask questions about the social. From its very beginning, painting has been tightly interwoven with historical and social events. To say that painting is merely self-referential and regressive and therefore lacks authority and relevance today is an argument that is not media-specific, but based on content. As with any other aesthetic practice, painting requires a strong conceptual self-understanding in order to function as a tool within a broader social context.

(KI) We could also talk about the way painting was removed from the social and how painting’s qualities and painters’ intentions have been obfuscated by discourse.

(DEE) If a painting addresses a specific social situation, it is clearly no guarantee that the work will avoid labelling such as conservative or anachronistic. In many instances, art has been used to further quite dubious causes and obviously, that is something one has to take into account when using painting as a means for developing a particular aesthetic practice.

I am not using the medium in a purely self-referential way, unconscious of the negative aspects connected to painting. The way I see it, the knowledge of the negative connotations related to painting seems to strengthen the possibility of working with it as a medium in an analytical and self-reflective manner.

(KI) What about time and slowness?

(DEE) There is a wide variety of speeds connected to painting, ranging from purely mechanical operations such as stretching and priming the canvas, to high-risk operations where everything is at stake. Or it can simply be the intellectual and visual pleasure of deciphering its many languages.

There is a certain temporal sensibility that informs and enters the artwork on many different levels. The experience of great art is always closely linked to an element of heightened awareness of time. When I was around 20 I visited the Capitoline Museum in Rome where they have a small painting by Velasquez entitled Unknown Gentleman with Blue Collar. I remained standing before that work for a long time without really having decided to do so. The painting somehow insisted and a very exact experience of time was given to me.

I have kept a postcard of this painting to remind me of a unique moment and a certain feeling of losing oneself. My experience with the Velasquez painting was one of abandonment and the realisation that it is in the absence of time that time gains its significance.

(KI) You have worked on a series of paintings called Sinthome, a title which relates to a term coined by Jacques Lacan. Did you read a lot of Lacan?

(DEE) I first came across Lacan in various art-related texts. His writing often analyses the things in life which are impossible to analyse - this is of course a highly relevant practice in relation to art.

Sinthome, if I understand Lacan correctly, does not constitute the opposite of a symptom, but rather signifies a highly explicit feeling that miraculously seems to escape appellation. The moment you try to define it, it slips away. You are confronted with the consequence of having posed the wrong question, as the object simply withdraws.

(KI) In a way, your works are manifestations of Sinthome on several levels - optically and conceptually - and it is as if they do not really need that title.

(DEE) I use the term Sinthome for a specific reason. I find highly descriptive titles problematic, nevertheless I like titles that refer to personal experience. The term Sinthome encompasses both the personal and the highly analytical, demonstrating a subtle balancing act rather than a compromise.

(KI) Does seriality have a specific meaning for you?

(DEE) I would prefer the term 'sequence' since seriality for me is somehow restricted to certain Minimalist strategies such as repetition and neutrality. Sinthome is an open project where the canvas ideally functions as a projection surface for incorporating a wide range of visual information. The individual paintings that comprise the sequence are not related through genre but through the method in which the different visual sources are brought together and worked through.

Kari Immonen

The Stop for a Moment exhibition series examined different ways of dealing with the problematics and possibilities of painting. Each of the three exhibitions were accompanied by a catalogue with an introductory essay, artists' interviews and illustrations highlighting the multifaceted ways of working with 'painting proper'.

Stop for a Moment - Painting as a Place to Be

Edited by Kari Immonen, Mika Hannula and Mitro Kaurinkoski

Curators: Kari Immonen and Mika Hannula

NIFCA Publication 11

Published by NIFCA, 2002

ISBN 951-97927-9-1

--------------------------

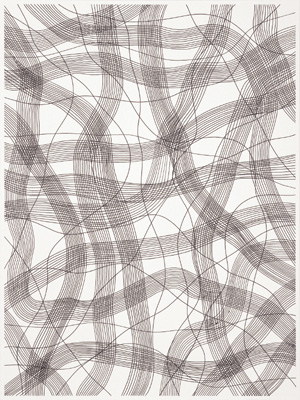

Drawing to Painting and back

EVENING DRAWINGS

Interview with Dag Erik Elgin

www.youtube.com/watch?v=JJqYzgQvaJk

The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design

Editor: Gavin Jantjes 2012

Konstens frågeformulär: Konsten.net 2016

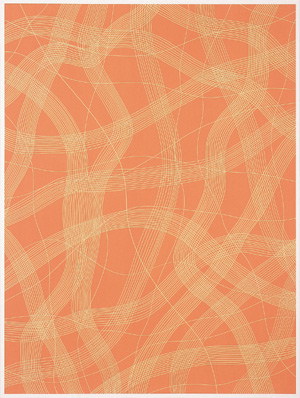

Balance of Painters: Carnegie Art Award 2014

Drawing to Painting and back : youtube.com/watch?v=JJqYzgQvaJk

Sinthome I-III 200x150 cm: NIFCA 2002/sic!(Stavanger Int Coll)

Sinthome II-III, 200x150 cm: NIFCA 2002/sic!(Stavanger Int Coll)